History

|

Newfoundland History |

|

[This text was written in 1949. For the full citation, see the end of the text. Parts in brackets [...], images and links have been added by Claude Bélanger.]

The influence of mercantilism was important in shaping the patterns of the early fisheries. Although the Portuguese, Spanish, and French were among the first to use the island as a base for fishing, they were gradually displaced by the more aggressive fishermen from the west of England who began visiting the island in force after 1550. Lack of solar salt forced the English to use the beaches along the coast to dry their catches before exporting them; this practice was the principal reason for the west country's opposition to settlement. With the defeat of the Spanish armada, the position of the west country interests was strengthened and pressure began to be exerted to obtain the support of parliament in preventing settlement. In these endeavours, the private interests of the west country fishermen coincided with those of mercantilistic England: exploitation of the fisheries was regarded by England as an ideal method of extracting new-world specie from Catholic Spain, as well as a method of training seamen. Thus the claims of the powerful west country group gained sympathy in parliament in the seventeenth century and found expression in a series of edicts designed to discourage settlement on the island as much as possible.

The English colonizers were forced to turn their attention to the mainland, particularly to New England, where settlement grew rapidly in the early seventeenth century. The productivity and aggressiveness of the New Englanders meant that patterns of trade began to emerge which had a significant influence on Newfoundland's development. New England found ready markets in the West Indies for her agricultural produce, in exchange for sugar and rum; Newfoundland came to be regarded as a good source of English bills of exchange and the New Englanders pressed for increased settlement of the island, in the hope of increased trade. Thus in the New Englanders, the west country interests met their first real opposition.

When, in the early 1860's, federation of the provinces of British North America became a definite prospect, Newfoundland showed considerable interest, and even sent two representatives to the Quebec conference in 1864. Ultimately, however, both economic and political factors conspired to keep her out of the federation. Unlike the provinces of British North America, Newfoundland had no heavy debt, no pressing railway problem, no immediate fear of United States hostility. Nor could she hold out much hope of broadening her markets through federation; indeed, in her only important export, codfish, she was in direct competition with Nova Scotia. Consequently, by 1869, the whole question was shelved and was not reopened until the mid-1890's.

The intervening period was one of general prosperity for the island, characterized by the further broadening of the bases of economic activity. Advances were made in farming and mining. A transinsular railway line was completed in a large semi-circle connecting St. John's with Port aux Basques in 1896. As was the case in Canada, construction was slow and uncertain and was only brought to completion by substantial government subsidies and land grants. The building of the railway generated considerable subsidiary activity, and numerous smaller types of enterprise sprang up, most of them locally managed and financed.

The disastrous

bank failure of 1895, however, put an end to the period of prosperity and

foreshadowed the chronic difficulties which have beset Newfoundland's economy

ever since. The immediate crisis was precipitated by the return of the bills

drawn on an English firm, one of whose members had died. A deeper reason,

however, lay in the inherent instability of Newfoundland's economy, stemming

from her too great dependence on the fishing industry. On December 10, 1894,

the Union and Commercial Banks, both local enterprises incorporated in 1854

and 1857 respectively, were forced to close their doors. Since the Union Bank

was the financial agent of the government, its failure was a serious blow

to the public credit. Unable to meet interest charges on the public debt,

the government turned first to Britain, then to Canada, for assistance. Britain,

however, would do nothing without first appointing a royal commission, and

this Newfoundland refused, largely through fear of losing her responsible

government. Negotiations with Canada, conducted at the Ottawa

conference of 1895, were equally unsuccessful, Newfoundland's renewed

interest in federation being thwarted by disagreements on financial grounds.

Failure of these efforts rendered the island's credit position even more precarious,

and only the forthright action of Robert

Bond, the colonial secretary, in raising loans on private money markets

in London saved the country from financial chaos. Two Canadian banks, the

Bank of Montreal and the Bank of Nova Scotia, opened branches in St. John's

in 1895, and established the Newfoundland currency on the basis of the Canadian

dollar.

Examples of Newfoundland silver coins: the 50¢ was issued

in 1882,

the 5¢ was minted at the beginning of the Great Depression

and

the 10¢ in 1938. For a history of Newfoundland's banking

institutions and currency

consult this

page.

World

War I brought a period of prosperity to Newfoundland, mainly because of

the prosperous condition of the fishing industry. Prices were high and the

demand was steady. Over-optimism and over-expansion characterized economic

activity, however, and the cultivation of land fell off. The result was an

inflationary period immediately following the war, followed by a depression

in the early twenties. The chronically unprofitable railway had to be taken

over by the government in 1923, along with steamship and telegraph services.

The rise of economic nationalism in many European countries brought renewed

hardships to the fishing industry and emphasized once again the necessity

of greater diversification in the country's economy. Increased competition

was encountered from Norway, Iceland, Spain and Italy. Iron

ore mining on Bell island, begun in 1895, slackened during this period

in response to a decline in the Nova Scotia steel industry.

The twenties saw new efforts at diversification. An

extensive highway program was undertaken in 1924; the Corner

Brook paper mill was completed in 1925; the output of mines, forests,

and agriculture were generally increased. But such efforts were now pursued

only at the cost of heavy capital imports and foreign borrowing. Government

provision of public utilities to support industrial diversification, combined

with her railway deficits and the costs of post-war demobilization, doubled

the public debt between 1920 and 1930. Although diversification had lessened

the country's dependence on the fishing industry, she remained as dependent

as ever on foreign markets, and demand for her products was still extremely

sensitive to world economic conditions. In general, servicing of the debt

during this period had to be financed by further borrowing abroad.

The depression

of 1929 struck Newfoundland with cruel

severity. A sudden shrinkage of exports, combined with increasing demands

on the public treasury, brought the country to the brink

of ruin. Wages fell drastically; unemployment was increased by the disappearance

of opportunities for seasonal employment outside the country, and relief expenditures

rose to unprecedented heights. Deficits, piled up until in 1933 the national

debt was over $100 millions, 95 per cent of it held outside the country, particularly

in the United Kingdom. Finally, in 1933, a royal

commission was appointed at Newfoundland's request, to report

on the situation. As a result of this investigation, Newfoundland relinquished

responsible government and placed itself under a commission

government in 1934.

World

War II did much to improve Newfoundland's credit position. American and

Canadian defence expenditures were an important factor in reducing the total

debt from $101 millions in 1931 to $88 millions in 1945. In addition, the

average interest rate had fallen from 5 to 3 per cent. But these favorable

factors should not obscure the fact that Newfoundland's peacetime debt position

since 1920 has been one of persistent deficit and the future holds no definite

prospect that the situation will be changed. The inexorable facts of meager

natural resources, low productivity and consequent low taxable capacity, have

still to be taken into account in any attempt to estimate future government

debt.

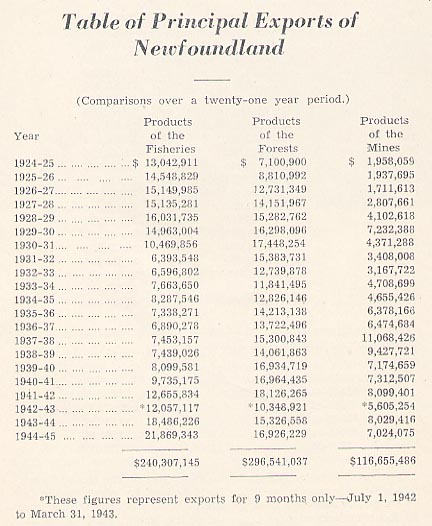

The progress of diversification of industry brought

the pulp-and-paper industry into position as the foremost contributor to national

income in the late thirties, although the fishing industry still provides

livelihood for the largest number of people. Mining holds third place in producing

national income. Agriculture and manufacturing are still geared to the local

markets. Exports are still the basis of the country's livelihood, and a stable,

multi-lateral world trading system is thus of prime importance.

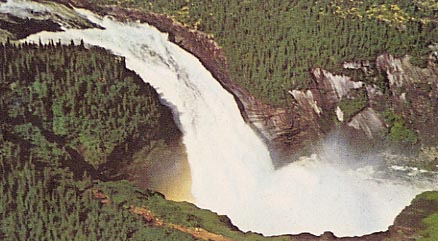

Since this text was written in 1949, it does not discuss

a great resource of Newfoundland that is drawn

from the Labrador

region: hydro-electricity.

Picture above is Churchill

Falls.

Over a 32 km distance, the river level falls more than 300m

with a drop

of over 75m at the falls themselves. In the 1970's, the river

was

harnessed and since 1974 it has been producing vast amounts

of power that is

directed toward Montreal and the United States. Churchill

Falls has a generating capacity

of over 5,225,00 kw, one of the largest in the world. The

contract signed with Hydro-Québec

has been the subject of much debate between Newfoundland and

Quebec. This

debate is an extension of the Quebec-Labrador

boundary dispute.

[See the Churchill

Falls Corporation Limited (Lease) Act, 1961,

Hydro-Québec

v. Churchill Falls, 1988, and the speech

of Brian Tobin,

Premier of Newfoundland, explaining the position of his province

in 1996]

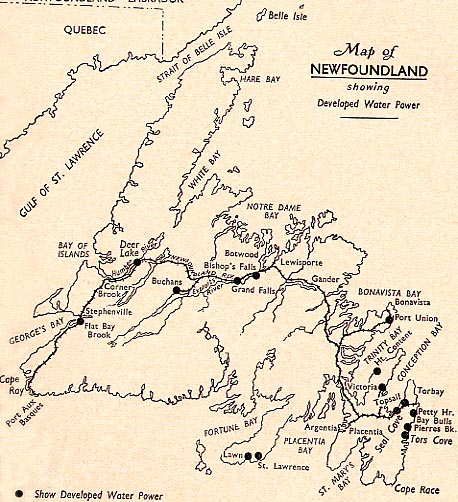

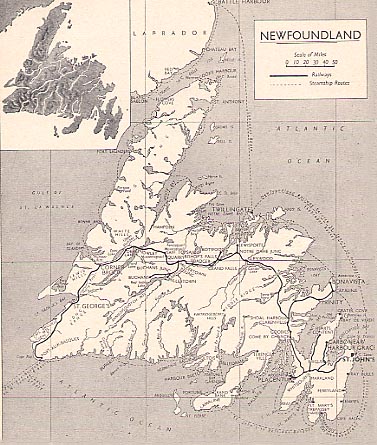

Newfoundland map of the early 1950's showing the

hydro-power plant developments.

For recent statistics, see the Census of Newfoundland,

1945, and numbers of Foreign Trade, published by the Canadian department

of trade and commerce. For an extensive bibliography of the subject, see the

appendix to R. A. MacKay (ed.), Newfoundland: economic, diplomatic, and

strategic studies (Toronto, 1946).

Owing to the structure and climate of the island, fertile

soils are rare in Newfoundland. The glacial till which covers the island is

poor in plant food, while the bleak climate results in soils marked by an

absence of bacteria and worms which are necessary to break down such humus

as may be present. Only by a lengthy process of manuring can the soils be

improved; hence there are no extensive croplands, but only small patches.

There are said to be only 4,000 farmers (2,809 in 1945 out of a total population

of 322,000), and they cultivate less than half of one per cent of the total

area. However, almost every fisherman has a small garden, where potatoes and

other vegetables are grown, and so about 40,000 people help to produce the

food of the population.

The chief farms, naturally, are close to the larger

centres of population. Thus there are many farms on the Avalon

peninsula, near St.

John's, and small areas of a few acres each are to be found near Bishop's

Falls and Grand

Falls. In the far south-west corner, along the Codroy valley, is the largest

area devoted to farms. Here soils and summer temperatures are more favourable

than in most parts of the island. Hay, potatoes, oats, and buckwheat are the

chief crops. Much of the hay is sold as feed for horses that are used in the

woods by logging companies. Some produce is sold and much more could be sold

profitably to the settlement of Port

aux Basques nearby, since it, as all other large settlements, has to import

almost all foodstuffs except potatoes and codfish. At some farms along Deer

lake, maize and pumpkins usually ripen, but such crops are exceptional.

To the north-west near Deer lake are many clearings in the forest, made after

soil surveys by the government, and here it is hoped that farmers will settle

and grow crops while earning wages through part of the year by cutting timber

for the paper mills.

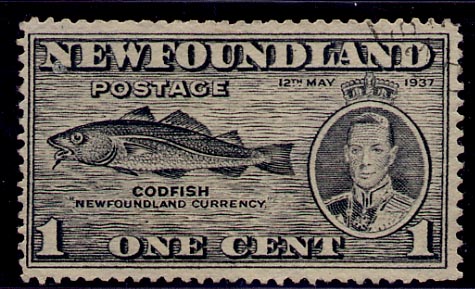

The cod fisheries have played a dominant rôle in the economic, political, and social history of' Newfoundland. The island is located in the northern part of a vast area, extending from New England to Labrador, in which cod is to be found in large numbers. Sharply affected by seasonal changes, it very early became the centre of a summer fishery in which the relatively smaller sizes of cod were taken and dried with solar heat and smaller quantities of solar salt.

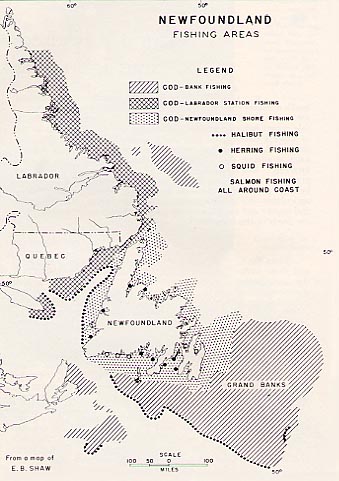

Map outlining the principal species and the main areas

where

Newfoundland fisheries were carried out until the

establishment of the moratorium

of 1992.

[Consult the issue of the Canadian

Geographic Magazine on this subject]

Prosecuting the fishery in Newfoundland and returning

to the west country with dried fish for export to Europe was gradually displaced

by the practice of carrying fish directly from Newfoundland to European markets,

especially in the. Mediterranean area. Fishing ships proceeding to Newfoundland

early in the spring, carrying on the fishery during the summer months and

taking the product to European markets, were faced with the problem of transporting

large numbers of men to Newfoundland for the fishery, then to the European

markets and back to the west country. Colonizers, represented by the London

and Bristol Company (1610), proposed to establish a settlement which would

enable men to stay over the winter, to carry on a resident fishery, and to

provide cargoes for sack ships for the Mediterranean markets. This proposal

and others similar to it were ruthlessly defeated by west country fishermen

who insisted on the rights of a free fishery which gave the first arrival

each year the position of admiral for the season. The difficulties of developing

agriculture, to supply food for winter settlements, further restricted the

growth of settlement in Newfoundland and favoured the migration of population

to New England.

Prosecuting the fishery in Newfoundland and returning

to the west country with dried fish for export to Europe was gradually displaced

by the practice of carrying fish directly from Newfoundland to European markets,

especially in the. Mediterranean area. Fishing ships proceeding to Newfoundland

early in the spring, carrying on the fishery during the summer months and

taking the product to European markets, were faced with the problem of transporting

large numbers of men to Newfoundland for the fishery, then to the European

markets and back to the west country. Colonizers, represented by the London

and Bristol Company (1610), proposed to establish a settlement which would

enable men to stay over the winter, to carry on a resident fishery, and to

provide cargoes for sack ships for the Mediterranean markets. This proposal

and others similar to it were ruthlessly defeated by west country fishermen

who insisted on the rights of a free fishery which gave the first arrival

each year the position of admiral for the season. The difficulties of developing

agriculture, to supply food for winter settlements, further restricted the

growth of settlement in Newfoundland and favoured the migration of population

to New England.

The rise of New England and its demand for European

goods led to the growth of trade with Newfoundland. As a result of this increase

in trade, settlement began to expand in spite of continued and more vigorous

efforts of the west country to check it. Partly as a result of restrictions

on settlement imposed at the instigation of the west country, men known as

byeboatmen

began to dominate the industry. They were brought on the fishing ships as

passengers each spring, operated a fishery in Newfoundland independently of

the fishing ships, and sold their product before their return to England in

the autumn. The fishing ships were in a sense compelled to serve as sack ships

carrying passengers to Newfoundland and the finished product to European markets.

Following the treaty

of Utrecht, in 1713, New England became even more important as a base

of supplies for Newfoundland and as a support to growth of settlement. Fishermen

were attracted to New England and to the more profitable operations carried

on by byeboatmen, and fishing ships were compelled to rely on resident fishermen,

particularly on Irish labor which filled the gap created by emigration. The

growth of settlement was accompanied by extension to the south to occupy territory

centering about Placentia,

which had been vacated by the French after 1713, and by the development of

the bank fishery. St. John's became the centre of a resident fishery; fishing

ships became to an increasing extent sack ships, or retreated, on the development

of new areas, beyond the effects of competition from St. John's.

After the treaty

of Paris, Labrador was annexed to Newfoundland. In 1765 regulations favoured

the development of its fisheries by fishing ships, but in the Quebec

Act of 1774 Labrador was returned to Canada, and attempts were made to

re-establish the system of grants existing before the introduction of a free

fishery. Expansion to the north was accompanied by the development of the

fur trade and of the salmon fishery. The outbreak of the American revolution

cut off supplies of goods from New England. Palliser's

Act in 1775, and other legislation, attempted to offset the effects by

establishing a system of bounties which improved the position of fishing ships

and restricted the resident fishery. [See the British

Report on Newfoundland fisheries in 1776.]

In the treaty of Versailles the French abandoned fishing

rights from Cape

Bonavista to Cape St. John in return for rights along the coast from Point

Riche to Cape Ray. They remained in possession of St.

Pierre and Miquelon. During the long period of wars ending in 1815, Newfoundland

became increasingly a centre of settlement, and the fishing ships practically

disappeared. Territory north of Cape Bonavista was rapidly occupied. The seal

fishery emerged and expanded rapidly. Until New England and France were able

to revive their fishing industries, Newfoundland had an important market advantage

which was evident in higher prices. The Maritime provinces replaced New England

as a base of supplies, and the migration of labor to New England was checked.

The increasing importance of settlement created demands

for the extension of political institutions. In 1832 provision was made for

representative

government, and emergence of responsible

government in 1854 was accompanied by the development of resistance to

French interests in Newfoundland. In an attempt to re-establish the fisheries,

France introduced a system of substantial bounties which accelerated the use

of the trawl system of fishing, in which a line to which was attached a large

number of hooks was set out and visited at frequent intervals. The system

required large quantities of bait, which was purchased to an important extent

by fishermen in St. Pierre and Miquelon from settlements on the south shore

of Newfoundland, and attempts were made in Newfoundland to check competition

from the French fishery by imposing restrictions on exports of bait. An agreement

between France and Great Britain in 1857, designed to settle the difficulties

arising from conflicts between French and English fishermen, was followed

by protests from Newfoundland and recognition of the fact "that the consent

of the community of Newfoundland is regarded by Her Majesty's government as

the essential preliminary to any modification of their territorial and maritime

rights". Recognition of Newfoundland's control over natural resources was

followed by various measures designed to restrict the French fishery and to

extend Newfoundland's territorial rights. In 1881 Great Britain conceded territorial

jurisdiction over the "French

shore" to the Newfoundland government. Newfoundland refused to ratify

an agreement between France and Great Britain in 1885 and passed bait legislation

in 1887. France and Great Britain established in 1889 a modus vivendi which

was renewed from year to year and was the object of continued protests from

Newfoundland. The controversy became more acute with the growth of a lobster

fishery and was finally ended by the purchase of French rights by Great Britain

in 1904.

The increasing importance of settlement created demands

for the extension of political institutions. In 1832 provision was made for

representative

government, and emergence of responsible

government in 1854 was accompanied by the development of resistance to

French interests in Newfoundland. In an attempt to re-establish the fisheries,

France introduced a system of substantial bounties which accelerated the use

of the trawl system of fishing, in which a line to which was attached a large

number of hooks was set out and visited at frequent intervals. The system

required large quantities of bait, which was purchased to an important extent

by fishermen in St. Pierre and Miquelon from settlements on the south shore

of Newfoundland, and attempts were made in Newfoundland to check competition

from the French fishery by imposing restrictions on exports of bait. An agreement

between France and Great Britain in 1857, designed to settle the difficulties

arising from conflicts between French and English fishermen, was followed

by protests from Newfoundland and recognition of the fact "that the consent

of the community of Newfoundland is regarded by Her Majesty's government as

the essential preliminary to any modification of their territorial and maritime

rights". Recognition of Newfoundland's control over natural resources was

followed by various measures designed to restrict the French fishery and to

extend Newfoundland's territorial rights. In 1881 Great Britain conceded territorial

jurisdiction over the "French

shore" to the Newfoundland government. Newfoundland refused to ratify

an agreement between France and Great Britain in 1885 and passed bait legislation

in 1887. France and Great Britain established in 1889 a modus vivendi which

was renewed from year to year and was the object of continued protests from

Newfoundland. The controversy became more acute with the growth of a lobster

fishery and was finally ended by the purchase of French rights by Great Britain

in 1904.

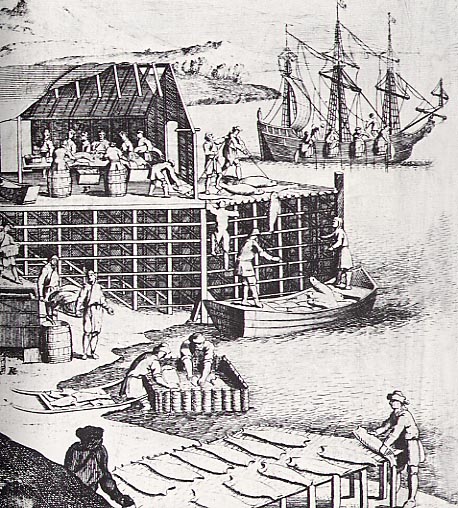

Detail from Eric Mill's map of North America published 1712-1714.

According to its author, it shows a view of a stage and the

manner of fishing for curing

and drying cod on the island of Newfoundland. The popular

scene contains

several inaccuracies: the type of ship used for fishing, the

fact that cod

and seals are harvested at the same time, the fish stage itself,

etc.

With responsible government Newfoundland pressed for

exclusion not only of France but also of the United States, Canada, and Great

Britain, from the fishery. Following the reciprocity

treaty (1855-1866) with the United States, Newfoundland introduced and

enforced regulations which rapidly brought to an end participation

of the United States in the Labrador fishery. During the period of the

treaty of Washington (1873-85),

Newfoundland became increasingly aggressive against American infringements

and after its termination Newfoundland attempted to negotiate the Blaine-Bond

convention with the United States, but was defeated by Canadian intervention.

A second attempt to secure reciprocal arrangements in the Hay-Bond treaty

was defeated by the American senate and was followed by renewed attacks on

participation of Americans in the Newfoundland fishery. Disallowance of legislation

against the United States by Great Britain was followed by protests from Newfoundland

and submission of the whole problem to the Hague tribunal, which reported

in favour of the position of Newfoundland. Finally, an attempt on the part

of Canada to secure a broad interpretation of rights on the Labrador was defeated

in a privy

council decision of 1927.

Exclusion of fishermen from foreign countries from Newfoundland

facilitated expansion of the local fisheries to the west coast and on the

Labrador. The high prices of cod during World War I were followed by a decline

and by increasing competition in European markets from cod produced more cheaply

by steam trawlers in Iceland and elsewhere; hence Newfoundland trade shifted

to West Indian and South American markets. Problems of centralized marketing

in purchasing countries were met by the establishment of marketing boards.

Recent developments have been the extension of marketing organizations, encouragement

of the fresh fish industries, exploitation of types of fish other than cod,

and establishment of a research centre. The number of people engaged in the

fishery decreased, between 1921 and 1945, from 65,000 to 32,000. [For a discussion

of the recent developments in Newfoundland fisheries, consult this

web site. Much material can be found in this bibliography.]

For a recent bibliography of the subject, see the appendix to R. A. MacKay (ed.), Newfoundland economic, diplomatic, and strategic studies (Toronto, 1946).

About 16,000 square miles, or approximately two-fifths of the area of Newfoundland is forested, mainly along the river valleys. Labrador has extensive forest areas along the coasts, but there has been no comprehensive inventory, and utilization is restricted to the requirements of the sparse population. In Newfoundland too, lumbering was at first on a small scale to supply local needs, and sawing was done by numerous small mills scattered along the coast.

There were

also, for some years, larger mills which exported lumber. The French Company

of Quebec, operating mills at Botwood

(1890-1900), was succeeded by the Exploits

River Company (1900-1906), which was absorbed by the Newfoundland Pine

and Pulp Company. The Lewis Miller Company of Scotland (1900-1903), with mills

at Millertown and Glenwood, was sold to the Newfoundland Timber Estates Company,

which shipped dimension stock from Lewisporte

to Argentina, and in 1905 was resold to Anglo-Newfoundland Development Company.

Central Forest Limited, which held limits on Rattling brook, Notre

Dame bay, and Norris arm, and mills at Norris arm, was sold to the A.

E. Reed Company which operated from Bishop's

Falls.

Most of the extensive, though scattered, stands of white

pine, upon which the lumbering industry was based, have been removed. The

present forests consist of white birch, which has value as fuel, and of pulpwood

species, so that lumbering has been replaced by the pulpwood industry.

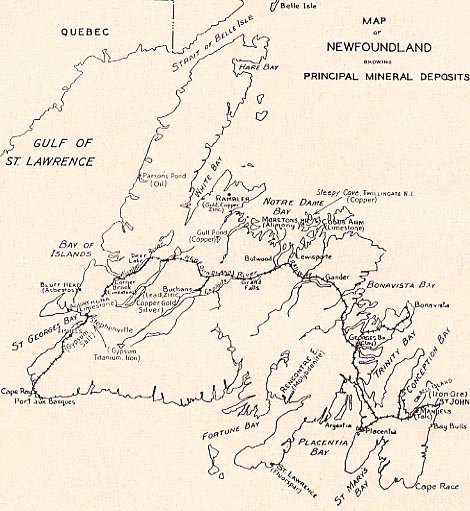

Mining in Newfoundland

[For an extensive discussion of Pre-Confederation mines

in Newfoundland, consult Wendy Martin's Once

upon a Mine. The Story of Pre-Confederation Mines on the Island of Newfoundland.]

Since much of the island of Newfoundland consists of very ancient rocks, a

rich supply of metals is to be expected. Unfortunately only two large fields

are in operation at present, the Buchans

copper mine; and the Wabana iron mine on Bell

island. Between 1888 and 1912 large amounts of copper were obtained at

Tilt Cove, but these mines are now unimportant: Discovery of the rather complex

lead-zinc-copper ores at Buchans in the Exploits valley was made as early

as 1905, but it was not until 1928 that the flotation process enabled these

ores to be treated satisfactorily.

The most interesting, mine is Wabana, situated on Bell

island in Conception bay, only 20 miles north-west of St.. John's. There ere

are three beds of hematite iron ore which dip at 'a shallow angle under the

sea to the north, and many of the workings are under the sea. The first cargo

of iron ore left Bell island in 1895 to be smelted with the coal of Pictou,

Nova Scotia. In 1899 the Dominion Steel Company purchased the mines, and the

ore is now carried to Sydney, Nova Scotia, and smelted at the large steel

works in the north-east of that city. There are said to be from 2.5 to 10

thousand million tons of ore available. In 1947 the mine produced 1,280 thousand

tons of iron ore.

Newfoundland map of the early 1950's showing the mineral

wealth of the island

Coal, though not abundant, occurs in folded rocks in

the western depression near. Deer lake and the Codroy, but very little mining

has been done. Fluorspar is found on a commercial scale on Burin

peninsula. Manganese is reported from Avalon (near Trepassey), and molybdenum

in places on the south coast. There are oil shales near Deer lake which may

be used to produce oil when extraction becomes economically feasible. Marble

is found on the east coast of the Long Range peninsula, but is not regularly

quarried.. Iron ore was discovered in Labrador in 1895, and large deposits

of high-grade ore have been mapped along the upper Kaniapiskau river, but

development awaits construction of a railroad by which ore could be, shipped

south to the St. Lawrence river.

Bibliography:J.

B. Jukes, Excursions in and about Newfoundland (London, 1842),; A.

Murray, Report on the geology of Newfoundland (Montreal, 1866); J.

P. Howley, Coal deposits of Newfoundland (St. John's, 1918) ; C. Schuchert,

Stratigraphy of western Newfoundland (Washington, 1934) ; A. K. Snelgrove,

Mines and mineral resources of Newfoundland (St. John's, 1938) ; G.

Taylor, Newfoundland, a study of settlement (Toronto, 1946).

The forests of Newfoundland now consist principally

of pulpwood species: balsam fir, white and black spruce, and some second growth

larch. Consequently the lumbering industry, which used white pine, has given

way to a pulp-and-paper industry whose exports, in 1948, amounted to $ 40,000,000,

or about half of all exports.

Production first began when the Newfoundland Wood Pulp

Company, incorporated in 1897, built a sulphite mill with a daily capacity

of 20 tons at Black River, Placentia bay. The mill, after operating for five

or six years, was discontinued because of a shortage of water power, but had

provided valuable information on possibilities of the industry on the island.

Other ventures followed, and production is now [1949] in the hands of two

large companies, the Anglo-Newfoundland Development Company and Bowater's

Newfoundland Pulp and Paper Mills.

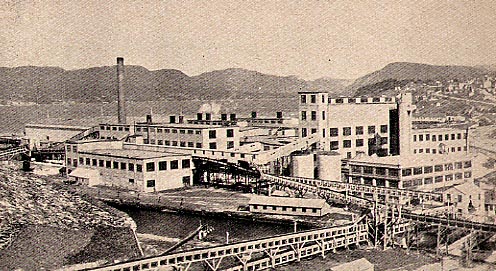

Bowater's holds limits amounting to 11,000 square miles,

mostly along the north-west coast and in the Codroy, Humber, and Gander basins.

The mill, erected at Corner

Brook in 1923 by the Newfoundland Power and Paper Company and bought by

Bowater's in 1936, has at present a daily capacity of 1,000 tons. The power

house is at Deer lake. Shipping is done from Corner Brook and, in the winter,

from Port aux Basques.

View of the Bowaters pulp and paper mill of Corner Brook

(early 1950's)

The Anglo-Newfoundland Development Company, incorporated

in 1905, holds limits in the Exploits

valley, the Terra

Nova basin, and along the west shore of White bay, about 7,500 square

miles in all. Power is generated at a dam across the Exploits river. A mill

at Grand

Falls, with daily capacity of 120 tons, was completed in 1909, and the

present capacity is 600 tons. A groundwood mill, which was operated by A.

E. Reed Ltd. at Bishop's

Falls between 1909 and 1928, is now owned by Anglo-Newfoundland, and the

ground-wood is pumped to the Grand Falls mill. The mills are connected by

railway to the port of Botwood.

The two large companies provide seasonal employment

in the woods for some 5,000 men, and steady employment for more than 3,000

in the mills.

Bibliography.See Forest resources and industries, a memorandum prepared for the British Empire Forestry Convention (London, 1920); J. Turner,. Forests of Newfoundland in J. R. Smallwood (ed.), Book of Newfoundland (St. John's, 1937); R. A. MacKay (ed.), Newfoundland: economic, diplomatic, and strategic studies (Toronto, 1946) ; G. Taylor, Newfoundland (Toronto, 1946).

Construction of the first railroad in Newfoundland began

in 1881, when the Newfoundland Railway Company undertook to build a narrow

gauge line from St. John's to Harbour Grace. There was considerable opposition

to the railway, and in the summer of 1881 several hundred inhabitants of the

south shore of Conception bay, persuaded by agitators that their possessions

were being taken away from them, armed themselves, and in a riot which has

become known as the "battle of Foxtrap", put a temporary stop to construction

of the line. After completing some 60 miles of track, the company defaulted,

and the line reverted to English shareholders who completed the line to Harbour

Grace. Daily service, six days a week, from St. John's to Salmon Cove, was

begun in 1884.

The Whiteway

administration, which had inaugurated the railway policy, was replaced

in 1885 by the Thorburn

government, which built and in 1888 opened a railway from Whitbourne to

Placentia. Construction was managed by the government, and had been carried

forward to Rantem in 1889 when it was decided by Sir William Whiteway, who

had returned to the premiership to have the line completed by a contractor.

Map of the railway and ferry lines of Newfoundland

in the early 1950's

The contract was awarded to Robert

Reid in 1890, and the road had been completed, through Norris Arm to Port

aux Basques, by 1897. Under an agreement signed in 1893, Mr. Reid undertook,

for a grant of 5,000 acres for each mile of track, to operate the railroad

for ten years; and the first train to cross the island left St. John's on

June 29, 1898.

By another contract, the "Reid deal" concluded by the

ministry of Sir

James Winter in 1898, the Reid Newfoundland Company was given further

grants of land and gained control not only of the railway but also of the

St. John's dry dock, the telegraph lines, and the coastal mail and passenger

service.

This Reid contract was modified by a new agreement with

the government of Sir

Robert Bond in 1901, but the company continued to operate the railway

and steamship services. In 1910 the company contracted with the government

of Sir

Edward Morris to build six branch lines, and four of the lines were in

operation by 1915. In 1920 the Reid Newfoundland Company, then operating at

an annual loss of about $1,500,000, appealed to the government for financial

aid. In 1921, operation of the railway and steamship services was taken aver

temporarily by a government commission, and Sir George Burry, a former vice-president

of the Canadian Pacific Railway, was called in to make recommendations. Acting

upon his advice, the government appointed a general manager of the railway

to act under the supervision of the Reid Newfoundland Company, but the arrangement

led to a deadlock and finally, on July 1, 1923, for a consideration of $2,000,000,

the company and its subsidiary companies retired absolutely from all transportation

operations in Newfoundland.

This Reid contract was modified by a new agreement with

the government of Sir

Robert Bond in 1901, but the company continued to operate the railway

and steamship services. In 1910 the company contracted with the government

of Sir

Edward Morris to build six branch lines, and four of the lines were in

operation by 1915. In 1920 the Reid Newfoundland Company, then operating at

an annual loss of about $1,500,000, appealed to the government for financial

aid. In 1921, operation of the railway and steamship services was taken aver

temporarily by a government commission, and Sir George Burry, a former vice-president

of the Canadian Pacific Railway, was called in to make recommendations. Acting

upon his advice, the government appointed a general manager of the railway

to act under the supervision of the Reid Newfoundland Company, but the arrangement

led to a deadlock and finally, on July 1, 1923, for a consideration of $2,000,000,

the company and its subsidiary companies retired absolutely from all transportation

operations in Newfoundland.

The government improved the main line, and built a new

dock. The 1930's saw several of the branch lines abandoned. The construction

of large military bases on the island during World War II brought about heavy

increases in freight and passenger traffic, so that the railroad's revenue

tripled and, for almost the first time, met the cost of operation.

The Newfoundland Railway and Steamship Services in 1949

became known as Canadian National Railways, Newfoundland Services.

Roads.

Since the sea has served and still serves as highway

between settlements on the coast of Newfoundland, development of roads has

not been rapid. However, there are a number of highways, mainly gravel-surfaced,

in some districts, and new construction is under way.

On the west coast a gravel road loops around the head

of St.

George's bay from Flat Bay to Lourdes, and farther north, roads out of

Corner Brook run south to St. George's lake and north to Bonne bay. On the

north-east coast, a road loops from Leamington through Botwood, Grand Falls,

and Badger, and swings north to Hall's bay. On the south coast, there is a

road around the foot of the Burin peninsula. Another road, across the top

of the peninsula, from Terrenceville to Goobies, joins the new Cabot highway

which crosses the Rantem isthmus and links Bonavista with St. John's.

The most highly developed system of roads, of course,

is to be found on the Avalon peninsula. A coastal highway runs from Trepassey,

in the south, through St. John's and around to New Harbour, in the north-west.

There are, in addition, other highways and branches, so that most of the settlements

on the peninsula may be reached by road. The roads from St. John's to Portugal

Cove and St. John's to Carbonear

have been paved, and some paving has been done on the highway leading southward

from St. John's.

Sealing, once an important industry in Newfoundland,

is now mainly of historic interest.

The hunt takes place, between March 14 and May 1, off

the northern shores, during the northern migration of the hood and harp seals.

The principal objects of the hunt are the young seals, which are valuable

for their fat.

In the early days, winter residents caught seals with

nets along the shores. Later, small boats were used in the hunt, and later

still, sailing vessels. There are records of seal oil being exported as early

as 1749. Between 1830 and 1860 the average annual catch was close to 440,000

seals, and in the spring of 1855 there were 400 vessels and 13,000 men engaged

in the hunt. Steamships were first used in the hunt in 1863, and by 1880 had

replaced the sailing vessels. In 1906 there were twenty-five steamers, in

1936 only eight, and in 1945 only two went to the ice for seals.

In the early days, winter residents caught seals with

nets along the shores. Later, small boats were used in the hunt, and later

still, sailing vessels. There are records of seal oil being exported as early

as 1749. Between 1830 and 1860 the average annual catch was close to 440,000

seals, and in the spring of 1855 there were 400 vessels and 13,000 men engaged

in the hunt. Steamships were first used in the hunt in 1863, and by 1880 had

replaced the sailing vessels. In 1906 there were twenty-five steamers, in

1936 only eight, and in 1945 only two went to the ice for seals.

The decrease, apparently, is due to increasing costs

and decreasing demand.

The seal-hunt, coming as it does in early spring, provides

off-season employment for fishermen. Since sealing crews receive part of the

catch, competition for a berth on a sealing vessel has been keen, and until

the sealers' strike of 1902, crew members paid berth-money.

Since the hunt must take place among the ice-floes,

and since there is never any certainty of finding seals, the industry has

been a dangerous one for both crews and owners, and there have been many wrecks

and other disasters.

Bibliography.The authoritative record of the Newfoundland seal fishery is Chafe's sealing book, a collection of annual reports made by L. G. Chafe (third edition edited by H M. Mosdell, St. John's, 1923). Other useful works are C. Michael, The seal and herring fisheries of Newfoundland (Montreal, 1873); A. Kean, Old and young ahead (London, 1935); W. H. Greene, The wooden walls among the ice floes (London, 1933); R. A. Bartlett, Sealing saga of Newfoundland (National Geographic, July 1929); J. T. Callanan, The Newfoundland seal hunt in J. R. Smallwood (ed.), Book Newfoundland (St. John's, 1937), Meaney, Saga of sealing (Atlantic Guardian, 1945); J B. Jukes, Excursions in and about Newfoundland (London, 1842).

Shipbuilding has been carried on as a local industry

in Newfoundland for many years, mainly to supply vessels needed in the fisheries,

and since about 1920 there have been several larger vessels built for the

Atlantic trade. In 1942 the Newfoundland government established at Clarenville

a shipyard which built, first of all, ten wooden freighters of 300 tons. In

1947-48 the Clarenville yards, together with other shipyards on the island,

produced 56 vessels with a total tonnage of 2,663.

Telegraphs and Telephones.

Newfoundland figured largely in the early development

of transatlantic telegraphic service, and is the western terminus of several

submarine lines.

Telegraphic service between points on the island is

conducted by the government under the post-office department. In 1946, out

of 617 post-offices in Newfoundland and Labrador, 171 were telegraph offices.

Of these, 67 were land-line offices, 95 were wireless offices, and 9 were

both. On the Labrador coast, and in some other outlying areas, service is

by radio-telegraph.

It was from Cabot Tower, situated on top of Signal

Hill and overlooking the city

and port of St.

Johns, that Marconi

received from Cornwall, England, the first transatlantic wireless

message on December 12, 1901.

Telephone service, operated by the Avalon Telephone

Company, reaches most parts of the island ether by land-lines or by radio-telephone,

and forms a link between some of the smaller settlements and the postal telegraph

stations.

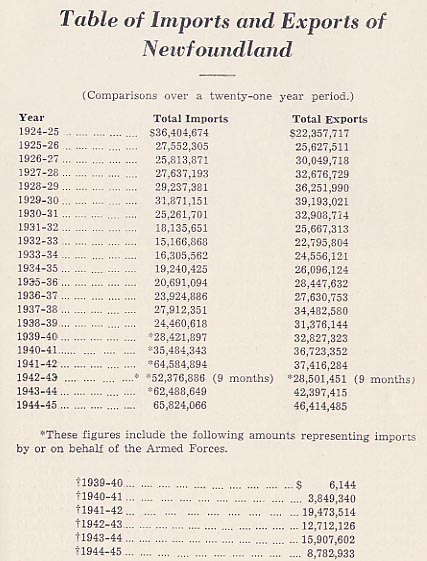

Though Newfoundland is often thought of as a one-industry

country, and though the fisheries do occupy a large proportion of the population, fisheryproducts

at present account for only about one-third of the island's exports.

Exports in 1947-48 amounted to $77,839,000, an all-time

record and more than double the amount for 1938. For the ten-year period,

exports and imports may be tabulated thus, in thousands of dollars

Exports Imports

1938 ............ 34,483 27,912

1940............. 32,827 28,422

1942............. 37,416 64,539

1944............. 42,397 62,485

1946............. 61,012 65,895

1948............. 77,839 105,059

Exports in 1947-48 were to the United States,

United Kingdom, Canada, and other countries, in this ratio? 26 to 13.5 to

9.5 to 28.5 ? and consisted of the following commodities:

salt codfish ... 20.9 per cent

other fishery products . . . . .15.1

minerals... 19.6

newsprint and newspaper.. 32.0

other forest products . .... . 6.9

other products ... 2.2

re-exports. ...

3.3

Imports during the same period were from Canada, United

States, United Kingdom, and other countries in this ratio 55 to 40.5 to 6

to 3.5 and consisted of the following commodities:

foodstuffs and beverages... 31.6 per cent

animal and vegetable products . . . 6.0

textiles and clothing . .. . 11.3

wood and paper .. . . . . . . 5.0

non-metallic minerals . .. 12.8

metals and manufactures 7.1

machinery and vehicles .. 17.6

chemicals and allied products 3.5

other products

5.1

Foodstuffs and beverages, the largest class of imports,

amounting altogether to $33,199,000, may be tabulated thus:

flour, meal, grains . . . . . . . .19.3 per cent

vegetables ... 4.8

fruit and juices . . . . . . . . 6.3

fresh meats... 7.3

preserved meats . . . . . . . . 18.6 per cent

sugar and products .. . . . . .13.3

milk and products. . . 7.0

oils and fats, edible .. . . . . . 6.3

tea, coffee, cocoa . . . . . . . .6.3

wines, liquor, beer .. . . . . . 4.5

other..

.. .... . .

6.3

Canada has been the largest supplier of Newfoundland's

imports but has absorbed relatively few of the exports, since most of Newfoundland's

exports have been competitive with Canadian products. Ordinarily Newfoundland

has had a small favourable trading balance with the United Kingdom, and a

strongly favourable balance with her principal fish markets: Puerto Rico,

Portugal, Italy, Jamaica, and Brazil. Since the development of the pulp-and-paper

industry, the highly adverse balance with the United States has been reduced.

Whaling,an industry which lapsed in Newfoundland during the 1920's, shows signs of being revived. In 1946 there were two whaling plants in operation, one in Hawke's harbour, Labrador, and one at Williamsport, White bay. There were 529 whales taken during the year, and the total export value of the products was $950,000 or triple that of the previous year's catch.

© 2004 Claude Bélanger, Marianopolis College |